Even the most flexible platform comes with certain built-in tendencies. Ethereum, for example, makes it easier to build organizations that are less centralized and less dependent on geography than traditional ones and certainly more automated. But it also creates a means for corporate ownership and abuse to creep ever deeper into people’s lives through new and more invasive kinds of contracts. To perceive the world through a filter like Ethereum is to think of society as primarily contractual and algorithmic, rather than ethical, ambiguous and made up of flesh-and-blood human beings. How this new ecosystem will take shape depends disproportionately on its early adopters and on those with the savvy to write its code — who may also make a lot of money from it. But tools like Ethereum are not just a business opportunity. They’re a testing ground for whatever virtual utopias people are able to translate into code, and the tests will have non-virtual effects. Idealists have as much to gain as entrepreneurs. As for any utopia, though, the power struggles of the real world are sure to find their way in as well.]]>

My latest at Al Jazeera, on Bitcoin’s most ambitious successor, Ethereum. This may or may not be the future, but for now it’s the hype:

]]>Even the most flexible platform comes with certain built-in tendencies. Ethereum, for example, makes it easier to build organizations that are less centralized and less dependent on geography than traditional ones and certainly more automated. But it also creates a means for corporate ownership and abuse to creep ever deeper into people’s lives through new and more invasive kinds of contracts. To perceive the world through a filter like Ethereum is to think of society as primarily contractual and algorithmic, rather than ethical, ambiguous and made up of flesh-and-blood human beings.

How this new ecosystem will take shape depends disproportionately on its early adopters and on those with the savvy to write its code — who may also make a lot of money from it. But tools like Ethereum are not just a business opportunity. They’re a testing ground for whatever virtual utopias people are able to translate into code, and the tests will have non-virtual effects. Idealists have as much to gain as entrepreneurs.?As for any utopia, though, the power struggles of the real world are sure to find their way in as well.

The forces that seem to have hastened Swartz's death were very much haunting the room. In the audience was a mischievous, greasy-haired hacker known as "weev," who faces as much as a decade in prison for embarrassing AT&T by publicizing a flaw in its system that compromised users' privacy. A member of Occupy Wall Street's press team handed out slips of paper about the case of Jeremy Hammond, an anarchist and Anonymous member who was in prison awaiting trial for breaking into the servers of the security company Stratfor. There was Stanley Cohen, a civil-rights lawyer representing some of Hammond's fellow Anons, and there was a T-shirt with the face of Bradley Manning, the soldier charged with passing classified material to WikiLeaks. Just behind weev sat Gabriella Coleman, an anthropologist, occasionally jotting notes in a notepad. She teaches at McGill University. Coleman first met Aaron Swartz when he was just 14, and over the years she had come to know many others in the room as well. Even more of them were among her 17,500-strong Twitter following or had seen her TED talk about Anonymous. Part participant and part observer, she began fieldwork on a curious computer subculture while still in graduate school. Now, more than a decade later, her work has made her the leading interpreter of a digital insurgency.Read the article at The Chronicle. And download Coleman's new book, Coding Freedom, for free at her website.]]>

My profile of anthropologist Gabriella Coleman in The Chronicle of Higher Education opens with a scene from the New York City memorial service for Aaron Swartz in January:

The forces that seem to have hastened Swartz’s death were very much haunting the room. In the audience was a mischievous, greasy-haired hacker known as “weev,” who faces as much as a decade in prison for embarrassing AT&T by publicizing a flaw in its system that compromised users’ privacy. A member of Occupy Wall Street’s press team handed out slips of paper about the case of Jeremy Hammond, an anarchist and Anonymous member who was in prison awaiting trial for breaking into the servers of the security company Stratfor. There was Stanley Cohen, a civil-rights lawyer representing some of Hammond’s fellow Anons, and there was a T-shirt with the face of Bradley Manning, the soldier charged with passing classified material to WikiLeaks.

Just behind weev sat Gabriella Coleman, an anthropologist, occasionally jotting notes in a notepad. She teaches at McGill University. Coleman first met Aaron Swartz when he was just 14, and over the years she had come to know many others in the room as well. Even more of them were among her 17,500-strong Twitter following or had seen her TED talk about Anonymous. Part participant and part observer, she began fieldwork on a curious computer subculture while still in graduate school. Now, more than a decade later, her work has made her the leading interpreter of a digital insurgency.

Read the article at The Chronicle. And download Coleman’s new book,?Coding Freedom, for free at her website.

]]>Apple CEO Steve Jobs returned to the stage earlier this month to announce a long-awaited new product: iCloud. “We’re going to demote the PC and the Mac to just be a device,” he said. “We’re going to move your hub, the center of your digital life, into the cloud.” No longer will the data that circumscribe our lives, from our dental records to our unfinished novels, remain confined to the tangible shells that presently contain them. They’ll live elsewhere, up there, in a better place. Apple may be the latest to try, but no company has puffed out more clouds than Google. All of the Google services so many of us depend on — Gmail, Docs, Calendar, Reader, YouTube, Picasa — lure our electronic selves, bit by bit, out of our computers and up into the cloud. If the cloud is a heaven for our data, a better place up in the sky, then Google is, well, kind of like God. But what kind of God? Some have actually tried to find out. Their efforts may appear to be mere intellectual exercises. But they raise serious questions about the nature of faith. In 2004, a Universal Life Church minister named Peter Olsen started the Universal Church of Google; last year, the misleadingly named First Church of Google appeared as well. But by far the most developed denomination is the Church of Google, founded by a reclusive young Canadian around 2006. It comes complete with scriptures, ministers, prayers, a holiday and, best of all, nine proofs that Google is “the closest thing to a ‘god’ human beings have ever directly experienced.”Read the rest: "Google as God."]]>

Over at The Daily—my latest?commentary on consumer technology gets theological:

Over at The Daily—my latest?commentary on consumer technology gets theological:

Apple CEO Steve Jobs returned to the stage earlier this month to announce a long-awaited new product: iCloud. “We’re going to demote the PC and the Mac to just be a device,” he said. “We’re going to move your hub, the center of your digital life, into the cloud.” No longer will the data that circumscribe our lives, from our dental records to our unfinished novels, remain confined to the tangible shells that presently contain them. They’ll live elsewhere, up there, in a better place.

Apple may be the latest to try, but no company has puffed out more clouds than Google. All of the Google services so many of us depend on — Gmail, Docs, Calendar, Reader, YouTube, Picasa — lure our electronic selves, bit by bit, out of our computers and up into the cloud. If the cloud is a heaven for our data, a better place up in the sky, then Google is, well, kind of like God. But what kind of God?

Some have actually tried to find out. Their efforts may appear to be mere intellectual exercises. But they raise serious questions about the nature of faith. In 2004, a Universal Life Church minister named Peter Olsen started the Universal Church of Google; last year, the misleadingly named First Church of Google appeared as well. But by far the most developed denomination is the Church of Google, founded by a reclusive young Canadian around 2006. It comes complete with scriptures, ministers, prayers, a holiday and, best of all, nine proofs that Google is “the closest thing to a ‘god’ human beings have ever directly experienced.”

Read the rest: “Google as God.”

]]>Real power was in the hands of a family of hereditary regents; the emperor's court had become nothing more than a place of intrigues and intellectual games. But by learning to draw a sort of melancholy comfort from the contemplation of the tiniest things this small group of idlers left a mark on Japanese sensibility much deeper than the mediocre thundering of the politicians. Shonagon [Sei Shonagon, a lady in waiting for the queen] had a passion for lists: the list of "elegant things," "distressing things," or even of "things not worth doing." One day she got the idea of drawing up a list of "things that quicken the heart."In the minds of computers, lists take on a more subtle beauty, a more mechanical one. The power of a computer lies partly in its incredible quickness in making and managing lists of data. I'd like to try a new kind of post at The Row Boat, a post of lists. This is the first of what may be many. They'll be brainstorming sessions put onto the wondrous internet in order to invite contributions from friends and passers-by. To inaugurate it, we'll start with a list of lists—more or less important lists that come to mind as indicators of all the different forms and all the different significances that a list can take. Please, for now and forever, offer your contributions in the comments or (if in secret) by email! […]]]>

I am a list-maker—about certain things. And I’ve learned a lot about friends by observing the things that they make lists of which I don’t. In my favorite film (after Star Treks I-VI, VII), Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, I discovered that lists can be an art form, as they were in eleventh-century Japan:

Real power was in the hands of a family of hereditary regents; the emperor’s court had become nothing more than a place of intrigues and intellectual games. But by learning to draw a sort of melancholy comfort from the contemplation of the tiniest things this small group of idlers left a mark on Japanese sensibility much deeper than the mediocre thundering of the politicians. Shonagon [Sei Shonagon, a lady in waiting for the queen] had a passion for lists: the list of “elegant things,” “distressing things,” or even of “things not worth doing.” One day she got the idea of drawing up a list of “things that quicken the heart.”

In the minds of computers, lists take on a more subtle beauty, a more mechanical one. The power of a computer lies partly in its incredible quickness in making and managing lists of data.

I’d like to try a new kind of post at The Row Boat, a post of lists. This is the first of what may be many. They’ll be brainstorming sessions put onto the wondrous internet in order to invite contributions from friends and passers-by. To inaugurate it, we’ll start with a list of lists—more or less important lists that come to mind as indicators of all the different forms and all the different significances that a list can take. Please, for now and forever, offer your contributions in the comments or (if in secret) by email!

- The six days of creation in Genesis

- The HTML elements <ul> and <ol>, of which so many parts of websites are structured

- Susan Sontag’s early journals

- The programming language Scheme, or its parent LISP (List Processing Language)

- The great Scholastic lists: deadly sins, theological virtues, sacraments, etc.

- Some of the earliest writing on Sumerian tablets were lists of goods

- For that matter, the Code of Hammurabi

- The list of Eugene McCarthy

- The Vatican’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum (“List of Prohibited Books”)

- Luther’s 95 Theses

- Shopping lists, to do lists

- The round robin, a list without a top

- Top ___ lists

- Honor roll

- “Did you make the list?”

- Endangered species list

- The lists of Sei Shonagon

- Phonebook

- The Open Directory Project

- Santa’s list

- The Fortune 500

- Angie’s List, Craigslist

- Blacklist

- Most wanted list

- This list (to keep things nice and recursive)

But then there is a catch. As anybody subjected to at least a name-dropping familiarity with Hegel (or more sexy contemporary exponents like Zizek and Derrida) knows, the two sides of any such binary imply each other, and indeed, rely on each other to know themselves. Moderation, that is, only makes sense to talk about when we have some idea of extremism to distinguish it against. This is a nice point to make in critical theory discussions, but it immediately gets lost in every other context, particularly when there is a scary extremism (e.g., terrorists) to be ruthlessly eliminated by well-meaning moderates.

The new atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett gave a short talk yesterday called “Public Education, Knowledge, and Visions for Non-toxic Religion.” Despite the Templeton Foundation-sponsored glossy fliers and the booking of a massive ballroom, there were far more empty seats than peopled ones. He took the opportunity to make his proposal for compulsory teaching about world religions in K-12 curricula, including home schools. The idea is that if everyone has to be aware of the basic facts of other religions, extreme forms of religion will disappear, since they can’t abide even knowledge of other religions. What Dennett didn’t say at the AAR but is clear from his books is that he hopes this proposal will spell the end of religion as a whole.

The new atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett gave a short talk yesterday called “Public Education, Knowledge, and Visions for Non-toxic Religion.” Despite the Templeton Foundation-sponsored glossy fliers and the booking of a massive ballroom, there were far more empty seats than peopled ones. He took the opportunity to make his proposal for compulsory teaching about world religions in K-12 curricula, including home schools. The idea is that if everyone has to be aware of the basic facts of other religions, extreme forms of religion will disappear, since they can’t abide even knowledge of other religions. What Dennett didn’t say at the AAR but is clear from his books is that he hopes this proposal will spell the end of religion as a whole.

To most AAR folks, this last step would be a counterintuitive one. What many (of us) dream of, in fact, is a world populated lovingly by nice religious moderates who abhor violence and intolerance while emphasizing love, sustainable lifestyles, and diversity. They are educated about each other and revel in difference as well as the cosmopolitan values everybody holds in common.

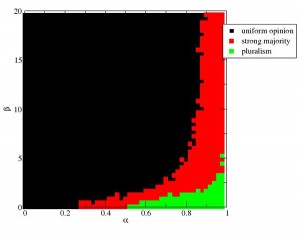

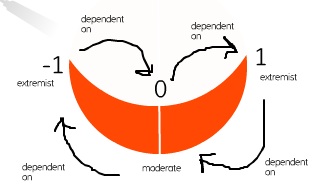

A new study, published a few days ago in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (vol. 11, no. 4 9), gives some interesting evidence supporting Dennett’s assumption. It is called “Can Extremism Guarantee Pluralism?” Using a computer simulation, the authors (two Italian physicists, Floriana Gargiulo and Alberto Mazzoni) modeled a community of software agents who exhibit a range of opinions between two extreme poles. The agents could interact with each other and change each other’s opinion. Extremists were those less willing to have their opinions changed by others, while moderates were more open to it. Imagine a simplified version of American politics: extreme Democrats and Republicans on each end, with moderates in the center, open to hearing others’ ideas out. They tinkered with the simulation in different ways to see how it reacted to different kinds of interaction between the agents.

A new study, published a few days ago in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation (vol. 11, no. 4 9), gives some interesting evidence supporting Dennett’s assumption. It is called “Can Extremism Guarantee Pluralism?” Using a computer simulation, the authors (two Italian physicists, Floriana Gargiulo and Alberto Mazzoni) modeled a community of software agents who exhibit a range of opinions between two extreme poles. The agents could interact with each other and change each other’s opinion. Extremists were those less willing to have their opinions changed by others, while moderates were more open to it. Imagine a simplified version of American politics: extreme Democrats and Republicans on each end, with moderates in the center, open to hearing others’ ideas out. They tinkered with the simulation in different ways to see how it reacted to different kinds of interaction between the agents.

The results are interesting. When like-minded agents weren’t permitted to cluster but instead forced to interact with others, the whole simulation turned into homogeneous mush. No diversity. All the simulated agents ended up agreeing. When extremists were allowed to be isolated from others, they ended up forming islands in what was still homogenous mush. Any way you slice it, a world dominated by moderates means no or no meaningful diversity.

The only way the simulation could produce stable diversity, it turned out, was when extremists were able to both isolate themselves and interact with the larger community, influencing moderates. Extremists enabled moderates to know, thereby, what doctrines they were moderate about, and thus to maintain some diversity in their interactions with other moderates in contact with a different set of extremists.

Dennett’s fellow new atheists, Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris, have alienated many by maintaining that religious moderates are in fact guilty for the crimes of extremists because the views they hold moderately legitimate those who hold similar views in more extreme forms. The JASSS study suggests that there is some truth to that claim. But just as disturbing, it points out how lines of influence go both ways; extremists and moderates both fundamentally enable each other.

Social psychologists, such as Jonathan Haidt, have lately been exploring how political preferences are informed by certain psychological dispositions that are more or less fixed in a person’s psychology. Thus it seems to be no accident that some people end up holding to quite rigid beliefs while others are more flexible. The range appears to be built into the normal spread of human variation—perhaps to secure the adaptive benefits of diverse opinions. For, as this study shows, diversity depends on interaction among both the fringes and the open-minded.

On the ground, this dialectic has consequences that may seem a little distasteful. If we moderates at the AAR are to enjoy diversity and openness, we might think twice about dedicating ourselves to eradicating extremisms as such. The psychological evidence suggests we probably won’t be able to anyway. And, in one area of life or another, most of us can’t help but find ourselves being extremists too.

(This reminds me of an earlier post about South Park.)

]]>Until now, The Row Boat was one of the few blogs out there not running on one of the major software platforms. Little Logger is a blogging program I built in early 2005, using Perl, static files, and a lot of workarounds. It has served very well since then. But in recent months, it has become clear to me that a change needed to happen. In particular, working with WordPress at The Immanent Frame has shown me what a powerful platform it can be.

The conversion process has reminded me why I stopped being a computer science major in college and switched to religion. I have been quite unable to think about anything else ever since I’ve started, and now I am worried about whether I will fall asleep tonight. This was a regular phenomenon in my computer science days—thrilling, but also perfectly exhausting. It makes me long to be thinking speculatively again, which hopefully can begin again tomorrow. The topic, presently, is Anselm.

]]>