Schneider tips his hand a bit with the title God in Proof. This isn’t, thank God, another book about the proofs for God’s existence, but rather a search, at once historical and personal, for the God that lives in proofs. The reversal — from proof for God to God in proof — is both linguistically nifty and philosophically important. It isn’t that the proofs for God lead us to God, but rather that God may be found — or may be shrouded — in the language of proofs. People see God in different settings. Some see God in song, others in nature, and others still in humanity as a whole. Schneider, in searching for his God, finds it revealed in the souls who historically sought out proofs for what they believed in.The review was also picked up two other wonderful blogs, Andrew Sullivan's Dish and 3 Quarks Daily. The quasi-New Atheist Jerry Coyne even says he'll read the book. Based on his earlier assessment of my writings on proofs, I don't expect he'll like it, but you never know.]]>

The filter blog Arts & Letters Daily is great, and it’s even greater that today it featured Robert Bolger’s excellent Los Angeles Review of Books review of God in Proof. Writes Bolger:

The filter blog Arts & Letters Daily is great, and it’s even greater that today it featured Robert Bolger’s excellent Los Angeles Review of Books review of God in Proof. Writes Bolger:

Schneider tips his hand a bit with the title God in Proof. This isn’t, thank God, another book about the proofs for God’s existence, but rather a search, at once historical and personal, for the God that lives in proofs. The reversal — from proof for God to God in proof — is both linguistically nifty and philosophically important. It isn’t that the proofs for God lead us to God, but rather that God may be found — or may be shrouded — in the language of proofs. People see God in different settings. Some see God in song, others in nature, and others still in humanity as a whole. Schneider, in searching for his God, finds it revealed in the souls who historically sought out proofs for what they believed in.

The review was also picked up two other wonderful blogs, Andrew Sullivan’s Dish and 3 Quarks Daily. The quasi-New Atheist Jerry Coyne even says he’ll read the book. Based on his earlier assessment of my writings on proofs, I don’t expect he’ll like it, but you never know.

]]> I’m a little perplexed by the new review of Thank You, Anarchy by Adam Kirsch, an editor of The New Republic among other things. Short of outright disapproving of my book, he replays a common liberal dismissal of Occupy. “For the vast majority of Americans, it was little more than a news story,” he begins, and he ends by claiming, utterly falsely, that “Schneider’s book suggests that the best way to understand Occupy is as a long, earnest holiday from reality, including the reality of politics.” I never once used the word “holiday” in that way; nor is that even what the book “suggests.” The last chapter concludes with a series of reflections on how to carry the ideals of Occupy into reality, and how people are doing so already. The book throughout strenuously insists that through Occupy, people experienced a return to the real politics of the needs of their communities, a break from the false politics of a deeply corrupted system. Kirsch’s reading, anyway, is suggestive of his assumptions, and, unfortunately, of my own failure to be clear enough to disabuse him of them. In that sense, the subtext of the review may be more revealing than the review itself.

]]>

I’m a little perplexed by the new review of Thank You, Anarchy by Adam Kirsch, an editor of The New Republic among other things. Short of outright disapproving of my book, he replays a common liberal dismissal of Occupy. “For the vast majority of Americans, it was little more than a news story,” he begins, and he ends by claiming, utterly falsely, that “Schneider’s book suggests that the best way to understand Occupy is as a long, earnest holiday from reality, including the reality of politics.” I never once used the word “holiday” in that way; nor is that even what the book “suggests.” The last chapter concludes with a series of reflections on how to carry the ideals of Occupy into reality, and how people are doing so already. The book throughout strenuously insists that through Occupy, people experienced a return to the real politics of the needs of their communities, a break from the false politics of a deeply corrupted system. Kirsch’s reading, anyway, is suggestive of his assumptions, and, unfortunately, of my own failure to be clear enough to disabuse him of them. In that sense, the subtext of the review may be more revealing than the review itself.

]]>NS: What was it like to be there in the midst of a revolution? TA: Even before my wife and I went, people kept saying to us, “Are you sure it’s safe?” Our Air France plane was actually cancelled. We were due to go on the 29th of January. We eventually left on the 12th of February, via Paris. We weren’t even able to go directly to Cairo, either. We had to go through Beirut. Then, all sorts of people starting ringing, again asking, “Is it safe? Are you sure you’ll be safe? We’ve heard all sorts of frightening things.” Remember the stories circulating early in the uprising about the prisons that had been opened and the police being withdrawn from the streets? That was what the fear was about. People wouldn’t believe me, but I was there for four months, almost, and I went all over town and never encountered any violence. I didn’t have any friends who could attribute violence to the uprisings—which isn’t to say it didn’t happen. Cairo contains eighteen million people, so it has always had its fair share of criminality. But ordinary life, actually, continued. Cafes were open, and shops, restaurants, and so on. You’d often hear that foreigners were in danger, or that ordinary life was impossible, but that is really not true. NS: Impossible, that is, without the control of the state and the police? TA: Exactly. There are elements in Egypt that were quite happy to circulate stories of unrest. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces talked again and again about the fact that we must have stability, which is then linked ominously to questions about the state of the economy. Since the economy suffers from the political instability in the country, they say, we shouldn’t have more demonstrations or strikes. But one of the things that emerged for me there, and which I’m trying to make sense of, was the constant flow of speculation, of suspicion, about who’s saying and who’s doing what.?Why are they doing this? Are they really doing it for good reasons? Is it the army? The Muslim Brothers?Is their presence or absence significant? Do they mean what they say?—You know, that sort of thing. I can’t claim to have made good sense of it yet, but, to me, this seems very important.We also discussed the transition from violent to nonviolent resistance, blasphemy laws, and even the end of the world. Particularly choice, too, is this passage, where he describes a conversation about colonialism with the great literary theorist Edward Said, whose successor Asad arguably has become:

I remember talking once a long time ago with Edward Said about empire and how it might be defeated. We were just sitting and having coffee, and at one point I responded to some of his suggestions by saying, “No, no, this won’t work. You can’t resist these forces.” So he demanded a little irritably: “What should one do? What would you do?” So I said, “Well, all one can do is to try and make them uncomfortable.” Which was really a very feeble reply, but I couldn’t think of anything else.]]>

What does it do to people, and to a society, to suddenly become revolutionary?

What does it do to people, and to a society, to suddenly become revolutionary?

I recently had the chance to speak with Talal Asad, one of the leading anthropologists alive today, about the experience of being in Cairo earlier this year as the revolution unfolded around him. Our conversation appears this week at The Immanent Frame. What stuck out for him, and which he was still trying to find the words for, was a subtle but utterly pervasive kind of suspicion, one that often ran in direct contradiction to the facts on the ground.

NS: What was it like to be there in the midst of a revolution?

TA: Even before my wife and I went, people kept saying to us, “Are you sure it’s safe?” Our Air France plane was actually cancelled. We were due to go on the 29th of January. We eventually left on the 12th of February, via Paris. We weren’t even able to go directly to Cairo, either. We had to go through Beirut. Then, all sorts of people starting ringing, again asking, “Is it safe? Are you sure you’ll be safe? We’ve heard all sorts of frightening things.” Remember the stories circulating early in the uprising about the prisons that had been opened and the police being withdrawn from the streets? That was what the fear was about. People wouldn’t believe me, but I was there for four months, almost, and I went all over town and never encountered any violence. I didn’t have any friends who could attribute violence to the uprisings—which isn’t to say it didn’t happen. Cairo contains eighteen million people, so it has always had its fair share of criminality. But ordinary life, actually, continued. Cafes were open, and shops, restaurants, and so on. You’d often hear that foreigners were in danger, or that ordinary life was impossible, but that is really not true.

NS: Impossible, that is, without the control of the state and the police?

TA: Exactly. There are elements in Egypt that were quite happy to circulate stories of unrest. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces talked again and again about the fact that we must have stability, which is then linked ominously to questions about the state of the economy. Since the economy suffers from the political instability in the country, they say, we shouldn’t have more demonstrations or strikes. But one of the things that emerged for me there, and which I’m trying to make sense of, was the constant flow of speculation, of suspicion, about who’s saying and who’s doing what.?Why are they doing this? Are they really doing it for good reasons? Is it the army? The Muslim Brothers?Is their presence or absence significant? Do they mean what they say?—You know, that sort of thing. I can’t claim to have made good sense of it yet, but, to me, this seems very important.

We also discussed the transition from violent to nonviolent resistance, blasphemy laws, and even the end of the world. Particularly choice, too, is this passage, where he describes a conversation about colonialism with the great literary theorist Edward Said, whose successor Asad arguably has become:

]]>I remember talking once a long time ago with Edward Said about empire and how it might be defeated. We were just sitting and having coffee, and at one point I responded to some of his suggestions by saying, “No, no, this won’t work. You can’t resist these forces.” So he demanded a little irritably: “What should one do? What would you do?” So I said, “Well, all one can do is to try and make them uncomfortable.” Which was really a very feeble reply, but I couldn’t think of anything else.

My associate could sense the difference immediately, instinctively, without knowing exactly why at first. An experimental-film critic from Los Angeles, she goes to screenings a lot, and she knew this was not the normal crowd. Afterward, she explained all the subtleties of their misbehavior. They didn’t applaud when you’re supposed to. There was talking and rustling around during the credits—a big no-no, apparently. These people were cliquey, but differently so. What she could sense, I was able to fill in with a little more data: the room was full of religion people. I know because I am one, I guess. (She is not.) First, I recognized one of my editors at a Catholic magazine. There was also a man with a badge from the American Bible Society. When we sat down, I heard the group of dashing, coupled young professionals in front of us discussing things one doesn’t expect most young professionals to be talking about, like grace and the Seven Deadly Sins and plans to give a sermon. Next, another dashing young professional raised his voice above the chatter. Tall, blond, and neatly-blazered, he welcomed us, said he hoped we would enjoy the film, and invited us to discuss afterward how we could collaborate and “mobilize” “our communities” around it. That was another difference between this and the usual screening. We weren’t there to criticize, but to mobilize.Read the rest at KtB.]]>

If you’re into getting worked up about semi-artsy movies, the one you’re supposed to get worked up about lately is Terrence Malick’s new The Tree of Life. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year. And got booed.

If you’re into getting worked up about semi-artsy movies, the one you’re supposed to get worked up about lately is Terrence Malick’s new The Tree of Life. It won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year. And got booed.

You’re especially supposed to get worked up, it seems, if you’re into religion. At Killing the Buddha, I’ve just published an essay about the experience of being faith-based-marketed to at a Tree of Life screening recently.

My associate could sense the difference immediately, instinctively, without knowing exactly why at first. An experimental-film critic from Los Angeles, she goes to screenings a lot, and she knew this was not the normal crowd. Afterward, she explained all the subtleties of their misbehavior. They didn’t applaud when you’re supposed to. There was talking and rustling around during the credits—a big no-no, apparently. These people were cliquey, but differently so.

What she could sense, I was able to fill in with a little more data: the room was full of religion people. I know because I am one, I guess. (She is not.) First, I recognized one of my editors at a Catholic magazine. There was also a man with a badge from the American Bible Society. When we sat down, I heard the group of dashing, coupled young professionals in front of us discussing things one doesn’t expect most young professionals to be talking about, like grace and the Seven Deadly Sins and plans to give a sermon.

Next, another dashing young professional raised his voice above the chatter. Tall, blond, and neatly-blazered, he welcomed us, said he hoped we would enjoy the film, and invited us to discuss afterward how we could collaborate and “mobilize” “our communities” around it. That was another difference between this and the usual screening. We weren’t there to criticize, but to mobilize.

Read the rest at KtB.

]]> I'm really excited to announce that my interview with Kathryn Lofton, one of the most creative and brilliant young scholars of religion around right now, is now up at The Immanent Frame. Katie is a historian by trade, but over the years she has also cultivated a powerful fascination with Oprah, leading to her new book: Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon. It's a must-read, an ironic yet completely heartfelt encounter with pop culture's most iconic woman.

Here's a bit of our conversation:

I'm really excited to announce that my interview with Kathryn Lofton, one of the most creative and brilliant young scholars of religion around right now, is now up at The Immanent Frame. Katie is a historian by trade, but over the years she has also cultivated a powerful fascination with Oprah, leading to her new book: Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon. It's a must-read, an ironic yet completely heartfelt encounter with pop culture's most iconic woman.

Here's a bit of our conversation:

NS: Do you feel some responsibility to confront what Oprah represents, in the form of an active, engaged social critique? KL: It is incredibly important that we—women, men, believers, heathens, citizens—think, and think critically, about the female complaint, especially as it takes this specific form in the public sphere. Oprah is not just Oprah—she represents what has come to be a naturalized logic for women’s suffering. I would be lying if I didn’t say that writing this book was, for me, an act of feminism. But I would say that it is more important to me that it be understood as an act of criticism connected to the deep tissue of our national political and economic imaginary. So yes, this is an act of social critique. For as much as the solo striving hungry female is the object here, it is the silence of her sociality—all the while making commodity of her social receipt and struggle—that disturbs me. On her message boards, everyone testifies, but they don’t form social communities, social insurrection, or social protest. The social is incredibly absent from Oprah, even as she praises the idea of girlfriends, of groups, of clubs. The social is a rhetorical formulation leaving women exposed in their extremity without any public held accountable.Read the rest at The Immanent Frame.]]>

I’m really excited to announce that my interview with Kathryn Lofton, one of the most creative and brilliant young scholars of religion around right now, is now up at The Immanent Frame. Katie is a historian by trade, but over the years she has also cultivated a powerful fascination with Oprah, leading to her new book: Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon. It’s a must-read, an ironic yet completely heartfelt encounter with pop culture’s most iconic woman.

I’m really excited to announce that my interview with Kathryn Lofton, one of the most creative and brilliant young scholars of religion around right now, is now up at The Immanent Frame. Katie is a historian by trade, but over the years she has also cultivated a powerful fascination with Oprah, leading to her new book: Oprah: The Gospel of an Icon. It’s a must-read, an ironic yet completely heartfelt encounter with pop culture’s most iconic woman.

Here’s a bit of our conversation:

]]>NS: Do you feel some responsibility to confront what Oprah represents, in the form of an active, engaged social critique?

KL: It is incredibly important that we—women, men, believers, heathens, citizens—think, and think critically, about the female complaint, especially as it takes this specific form in the public sphere. Oprah is not just Oprah—she represents what has come to be a naturalized logic for women’s suffering. I would be lying if I didn’t say that writing this book was, for me, an act of feminism. But I would say that it is more important to me that it be understood as an act of criticism connected to the deep tissue of our national political and economic imaginary. So yes, this is an act of social critique. For as much as the solo striving hungry female is the object here, it is the silence of her sociality—all the while making commodity of her social receipt and struggle—that disturbs me. On her message boards, everyone testifies, but they don’t form social communities, social insurrection, or social protest. The social is incredibly absent from Oprah, even as she praises the idea of girlfriends, of groups, of clubs. The social is a rhetorical formulation leaving women exposed in their extremity without any public held accountable.

]]>NS: The design arguments for God’s existence that you address in The Book of God are typically treated by philosophers and the public as sheer abstractions, or even scientific hypotheses; why treat them instead as literary creations? CJ: No one discipline owns the design argument and its critiques. Historically, the distinctions that people typically draw today among literature, philosophy, and theology just don’t hold up. Professional literary study, especially, has only been around for a hundred years or so. A thinker like David Hume, who is very important to the story I tell about design, did not think of himself as a philosopher but as man of letters: he wrote history, philosophy, and theology, and he served as a diplomatic secretary. This was a typical “literary” career. I try to restore some of that broad range to the topics I write about—though no diplomats have signed me up yet! NS: What’s an example of how you, as a scholar of literature, can shed light on a philosophical debate? CJ: In Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Philo, who is skeptical of design arguments, wins the battle, but Cleanthes, who supports them, wins the war. One thing Hume might be suggesting is that if you’re on Philo’s team, you’d best give up your belief that better arguments can win the day all on their own. Yes, the philosophical or conceptual idea of design seems rather abstract, but, at the same time, those arguments are lived and experienced by real people in real time. This is one thing Hume figured out—and it’s a literary point, if you want to put it that way: the rhetoric, the habits of mind, the practices of sociability that accompany what we could call the culture of design aren’t just window-dressing for some philosophical argument. Those things are the argument. That’s why the culture of design is easier to come at through literature rather than the history of philosophy—through practice rather than theory, if you will. We’ve misunderstood the way secularization works if we think that better arguments drive the discussion.

Today at The Immanent Frame, I interview Colin Jager, professor of English at Rutgers and an authority on natural theology in British romanticism. He’s the author of, literally, The Book of God. Our conversation touches on many things swirling through my mind in connection with the book I’m working on—design, debate, and the existence of God. Here’s a bit of the exchange with Jager:

NS: The design arguments for God’s existence that you address in The Book of God are typically treated by philosophers and the public as sheer abstractions, or even scientific hypotheses; why treat them instead as literary creations?

CJ: No one discipline owns the design argument and its critiques. Historically, the distinctions that people typically draw today among literature, philosophy, and theology just don’t hold up. Professional literary study, especially, has only been around for a hundred years or so. A thinker like David Hume, who is very important to the story I tell about design, did not think of himself as a philosopher but as man of letters: he wrote history, philosophy, and theology, and he served as a diplomatic secretary. This was a typical “literary” career. I try to restore some of that broad range to the topics I write about—though no diplomats have signed me up yet!

NS: What’s an example of how you, as a scholar of literature, can shed light on a philosophical debate?

CJ: In Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Philo, who is skeptical of design arguments, wins the battle, but Cleanthes, who supports them, wins the war. One thing Hume might be suggesting is that if you’re on Philo’s team, you’d best give up your belief that better arguments can win the day all on their own. Yes, the philosophical or conceptual idea of design seems rather abstract, but, at the same time, those arguments are lived and experienced by real people in real time. This is one thing Hume figured out—and it’s a literary point, if you want to put it that way: the rhetoric, the habits of mind, the practices of sociability that accompany what we could call the culture of design aren’t just window-dressing for some philosophical argument. Those things are the argument. That’s why the culture of design is easier to come at through literature rather than the history of philosophy—through practice rather than theory, if you will. We’ve misunderstood the way secularization works if we think that better arguments drive the discussion.

It's a common refrain that one hears among those of us looking to think responsibly about the world's religions: at bottom, they all have a common core, and the core is a genuinely good one.

That would be nice, but I've never really bought it. To be honest, I don't even think it would be nice. All we'd have to do is follow the correct kernel of our religions and we'd be golden forever, end of story. So much of the interesting, complex, and messy stuff that makes learning about religions and about people so engrossing might peel away in the name of unity. And often, when such universal perennialism gets wheeled out, it turns out to be in fact a surreptitious assertion of a particular tradition, to which all the others become subservient.

But when Karen Armstrong, the British dean of comparative-religion-for-the-people, claims that all religions are really about compassion, when she goes on to promulgate a "Charter for Compassion," and when TED throws its connections and tech savvy behind her, it's hard to be too much of a curmudgeon. Sure, such things have come and gone again and again in history—how often have we heard calls for World Peace in Our Time?—but no less are we probably still responsible for giving it another go. And if a bit of fascinating religious mayhem has to be quieted in the process, so be it. There will still be science fiction.

That said, I'm glad to have had the chance to interview Karen Armstrong at The Immanent Frame. What she proposes is certainly a brave effort to mobilize her years of studying and writing into action, into a movement. It also represents an important example of activism and organizing from precisely the spiritual-but-not-religious vantage point that is supposedly able to do neither.

It's a common refrain that one hears among those of us looking to think responsibly about the world's religions: at bottom, they all have a common core, and the core is a genuinely good one.

That would be nice, but I've never really bought it. To be honest, I don't even think it would be nice. All we'd have to do is follow the correct kernel of our religions and we'd be golden forever, end of story. So much of the interesting, complex, and messy stuff that makes learning about religions and about people so engrossing might peel away in the name of unity. And often, when such universal perennialism gets wheeled out, it turns out to be in fact a surreptitious assertion of a particular tradition, to which all the others become subservient.

But when Karen Armstrong, the British dean of comparative-religion-for-the-people, claims that all religions are really about compassion, when she goes on to promulgate a "Charter for Compassion," and when TED throws its connections and tech savvy behind her, it's hard to be too much of a curmudgeon. Sure, such things have come and gone again and again in history—how often have we heard calls for World Peace in Our Time?—but no less are we probably still responsible for giving it another go. And if a bit of fascinating religious mayhem has to be quieted in the process, so be it. There will still be science fiction.

That said, I'm glad to have had the chance to interview Karen Armstrong at The Immanent Frame. What she proposes is certainly a brave effort to mobilize her years of studying and writing into action, into a movement. It also represents an important example of activism and organizing from precisely the spiritual-but-not-religious vantage point that is supposedly able to do neither.

NS: Do you anticipate that the Charter will eventually translate into meaningful social change? KA: All religious teaching must issue in practical action. This is something that has become very clear to me during the last twenty years, which I have devoted to the study of world religions. The doctrines and stories of faith make no sense at all unless they are translated into action. This is one of the essential themes of my latest book, The Case for God, which was being written at the same time as we were composing the Charter. We were all convinced that somehow the Charter must be a call to action. There was no point in us all embracing one another on the day of the launch if there would be no practical follow up. We need compassion—the ability to put ourselves in other people’s shoes, to “experience with” the other—in politics, social policy, finance, education, and media. Unless we can learn to treat all nations and all peoples as we would wish to be treated ourselves, we are unlikely, in these days of global terror, to have a viable world to hand on to the next generation.Read more at The Immanent Frame.]]>

It’s a common refrain that one hears among those of us looking to think responsibly about the world’s religions: at bottom, they all have a common core, and the core is a genuinely good one.

It’s a common refrain that one hears among those of us looking to think responsibly about the world’s religions: at bottom, they all have a common core, and the core is a genuinely good one.

That would be nice, but I’ve never really bought it. To be honest, I don’t even think it would be nice. All we’d have to do is follow the correct kernel of our religions and we’d be golden forever, end of story. So much of the interesting, complex, and messy stuff that makes learning about religions and about people so engrossing might peel away in the name of unity. And often, when such universal perennialism gets wheeled out, it turns out to be in fact a surreptitious assertion of a particular tradition, to which all the others become subservient.

But when Karen Armstrong, the British dean of comparative-religion-for-the-people, claims that all religions are really about compassion, when she goes on to promulgate a “Charter for Compassion,” and when TED throws its connections and tech savvy behind her, it’s hard to be too much of a curmudgeon. Sure, such things have come and gone again and again in history—how often have we heard calls for World Peace in Our Time?—but no less are we probably still responsible for giving it another go. And if a bit of fascinating religious mayhem has to be quieted in the process, so be it. There will still be science fiction.

That said, I’m glad to have had the chance to interview Karen Armstrong at The Immanent Frame. What she proposes is certainly a brave effort to mobilize her years of studying and writing into action, into a movement. It also represents an important example of activism and organizing from precisely the spiritual-but-not-religious vantage point that is supposedly able to do neither.

NS: Do you anticipate that the Charter will eventually translate into meaningful social change?

KA: All religious teaching must issue in practical action. This is something that has become very clear to me during the last twenty years, which I have devoted to the study of world religions. The doctrines and stories of faith make no sense at all unless they are translated into action. This is one of the essential themes of my latest book, The Case for God, which was being written at the same time as we were composing the Charter. We were all convinced that somehow the Charter must be a call to action. There was no point in us all embracing one another on the day of the launch if there would be no practical follow up. We need compassion—the ability to put ourselves in other people’s shoes, to “experience with” the other—in politics, social policy, finance, education, and media. Unless we can learn to treat all nations and all peoples as we would wish to be treated ourselves, we are unlikely, in these days of global terror, to have a viable world to hand on to the next generation.

Read more at The Immanent Frame.

]]>My present travels in Costa Rica with the photographer Lucas Foglia, through a sequence of chance connections and exaggerated truths, landed us the opportunity to be in the press section at today’s meeting between (Nobel laureate) President Oscar Arias of Costa Rica and the two contenders for the presidency of neighboring Honduras. We understand our work here more under the auspices of art than plain reporting—to the point that we ultimately thought more about the press corps gazing upon the performances than the content of the acts themselves, whose Spanish we couldn’t fully understand anyway.

This was the scene: reporters gathered in a cordoned-off half-block of street in front of Arias’s house, with all their thick wires, cameras large and small, questions, computers, recorders, hook-ups, makeup, grumbles, and banter. There was a stage set up at the front of our pen, by the entrance to the house, surrounded by potted plants and guarded by tourist police in white shirts armed only with the friendliest-looking of clubs. Most press stayed all day, mainly waiting from morning through evening. We arrived in mid-afternoon. Not long after, at the back of the press area, on the opposite site of the press section from the prepared stage, a cluster of protesters arrived, bearing flags and banners in revolutionary red, shouting familiar slogans. There was a charge to the rear, pulling correspondents from their posts at the presidents’ stage. I joined.

Dozens of bored reporters finally had something to do, fixing their lenses and microphones and adrenaline on the passionate ones making so much noise through their loudspeakers. Against militarism. Against the powers that be and their inexhaustible corruption. One dressed as Che. An effigy burned. I let my voice recorder take in a speech from one of the ringleaders, far too fast for me to understand. I took too many pictures that have already been taken before in countless places, at countless protests. My hope was to find somewhere its unique vitality, doubtlessly somewhere, awaiting its capture by a sympathetic observer who could make this event really exist by recording it, by broadcasting it, by turning it from what it was to what it represents.

On the other side, the large, immovable cameras still awaited the presidents. They fixed on an empty stage, or on the door from which these men would emerge.

Will this sacred dissent be heard over the decorous speeches, I wondered? They were loud. We, among our cameras and our wires that ran under us like roots in a forest, were huddled between two competing performances, each competing for its presence in the final ontology of that moment. According to research I’ve seen in cognitive science, while people may be able to talk abstractly about the possibility of simultaneous things, “in fact” (says the science) no—in the intuitive processes of human minds, only one event can happen at any given time and be an event, fully. As gatekeepers of event-ness in media culture, the cameras adjudicated a contest of two events, one on either side of the street.

Each had its violence, each had its peace. On one side, a gracious act of conflict resolution among the heads of inevitably murderous states (even, one way or another, military-less Costa Rica). On the other, a riotous cry for an end to injustice and bloodshed.

But I should have expected what happened. Well in time for the actual arrival of the men, as I listened to (and recorded) a long speech about the tragedy of politics from a Honduran photographer, the protests calmly faded away. I didn’t see if it was police or simply being finished that did them in, though I suspect some eerie combination of the two. The air was clear and quiet for, not too long after, the arrival of the powerful.

We stayed only for the appearance by Roberto Micheletti, the leader of the Honduran coup, flanked by Arias. Micheletti spoke—something about elections and the rule of law—but I watched Arias intently. He has a wonderful expression on his face, apparently always. So sad, so stern, so mournful. Whatever he is, for whatever it could possibly be worth, he does look like he carries all the suffering of the world in his expression, as one perpetually in the presence of futility, either right there before him or, at least, during a fleeting moment of progress, in the corner of his eye.

But I don’t know if that’s worth anything at all. I didn’t even get a good picture of him. And I still have to read all the papers to figure out what’s (really, factually, politically) going on, and who I think is on the brave side of right and peace and justice, which is the only peace. On the evening Costa Rican newscast, it goes without saying, only one of the two performances appeared. Only one event, apparently, really happened.

(Photos and video are mine, not Lucas’s, by the way.)

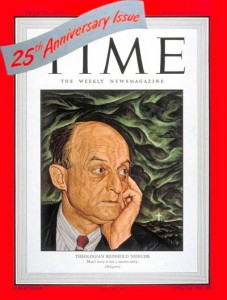

]]> During the years leading up to World War II, there was no deeper thorn in the side of Christian pacifists—by whom I mainly mean members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a community founded in the first months of the previous world war—than Reinhold Niebuhr. Having been formed as a pastor in working-class neighborhoods of Detroit, he led the FOR in the early ’30s. But he quickly began to question the wisdom of a radical commitment to nonviolence. As Hitler rose to power and the horror of his rule became apparent, Niebuhr doubted that the Christian conscience had any other option than containment by force. After the war, he became a defender of the U.S.’s Cold War posture against the Soviet Union. Today, his legacy has been cited by those eager for an end to the last decade of American hubris—Obama described him as “one of my favorite philosophers.” Though he asserted the need for armed conflict against hideous wrongdoing, he was motivated by the same skepticism of utopian thinking that left him no hope for the use of violence in the service of high ideals.

During the years leading up to World War II, there was no deeper thorn in the side of Christian pacifists—by whom I mainly mean members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a community founded in the first months of the previous world war—than Reinhold Niebuhr. Having been formed as a pastor in working-class neighborhoods of Detroit, he led the FOR in the early ’30s. But he quickly began to question the wisdom of a radical commitment to nonviolence. As Hitler rose to power and the horror of his rule became apparent, Niebuhr doubted that the Christian conscience had any other option than containment by force. After the war, he became a defender of the U.S.’s Cold War posture against the Soviet Union. Today, his legacy has been cited by those eager for an end to the last decade of American hubris—Obama described him as “one of my favorite philosophers.” Though he asserted the need for armed conflict against hideous wrongdoing, he was motivated by the same skepticism of utopian thinking that left him no hope for the use of violence in the service of high ideals.

In order to hone my recent thinking on peace and conflict, which have mainly been informed by Gandhian approaches, I’ve been working through Niebuhr’s 1940 essay “Why the Christian Church Is Not Pacifist,” collected in Robert McAfee Brown’s Essential Reinhold Niebuhr, published by Yale University Press. These are some reflections from an initial reading, thinking with Niebuhr and seeing where he takes me.

The Law of Love and the Condition of Sin

Niebuhr centers this discussion around the meaning of Christian love, which of course radical pacifists use as part of the basis of their position. He points out:

Christianity is not simply a new law, namely, the law of love. … Christianity is a religion which measures the total dimension of human existence not only in terms of the final norm of human conduct, which is expressed in the law of love, but also in terms of the fact of sin.

Sin is the reality of his “realism”—the cosmic fact that Christianity does not eliminate but embraces, reconciles, and forgives. Yes, violence is a sin against love, but that sin, too, has its place in Christian humanity. A few pages later, he states it another way: “The significance of the law of love is precisely that it is not just another law, but a law which transcends all law.”

The law of love does not represent a particular political strategy. Jesus didn’t baptize tactics, he baptized sinners. Love, therefore, is a posture within a sinful world, not an escape from it. The pacifists, Niebuhr would say, have taken a Pharisaical position, placing a norm of behavior above all else, including God.

One might distinguish, perhaps, between a law and a commandment. A law is a limit placed on actions, essentially coercive in nature. A commandment, of which Jesus said love is the highest, is something different. Commandments upbuild us, urging us toward creative action, in and through a world that includes both law and lawlessness.

Pacifism vs. Nonviolent Resistance

Next in the essay, Niebuhr asks how biblical modern nonviolence theory really is. In the first half of the twentieth century, peaceniks preached peace but generally lacked a method. But by the end of World War II, most believed they had found one in the work of Gandhi. The method of nonviolent resistance perfected in the Indian independence movement quickly began to take hold in the civil-rights struggle of black Americans. (For Niebuhr, as well as for Martin Luther King, the chief source was FOR member Richard Gregg, who lived with Gandhi in India before writing his classic The Power of Non-Violence.) Many Christian pacifists believed that Gandhi was in some sense a fulfillment of Christ’s promise.

Yet does Jesus’s scriptural example really have anything directly to do with Gandhian resistance? Jesus exhibited no interest in the overthrow of an unjust social order, beyond noting that its temples would crumble and its poor would always remain. He stood up for all sides of political divisions—centurions, tax collectors, oppressed Jews, and dejected prostitutes. Sure, he advocated taking blows without complaint, and did so himself; but he also spoke of swords and lashed out at merchants. Jesus’s witness was mainly pacifist, but it would be an exaggeration (and a disappointment) to say that this constituted Jesus’s essential message. Ascribing to him a Gandhi movement would be a stretch.

In the later books of the New Testament, the situation changes little. The text that has seemed to me the fullest in its resources for nonviolent resistance is 1 Peter (“For it is better to suffer doing good, if suffering should be God’s will, than to suffer for doing evil.” – 3.17), which appears to be a primer for martyrs-to-be. A technique is discussed, but there’s no indication that it should be applied beyond the particular circumstance of persecution. And it certainly takes little interest in bringing about change in the social order. God, not resistance, is the epistle’s cause of the change to come.

Niebuhr is very right to question the certainty of some that Christianity proscribes a particular tactic for dealing with political conflicts. It doesn’t. Still, that isn’t to say nonviolent resistance is decidedly un-Christian. It is a tool by which Christians may act Christianly. Just because Jesus did his healing through hand-waving magic tricks doesn’t mean (unless you’re a Christian Scientist) that Christians shouldn’t use hospitals to alleviate the suffering of others. Indeed, the establishment of hospitals for the poor was one of the great achievements of early Christianity, and continues to be.

Nonviolent struggle for justice is a way to enact the commandment of love, and a very good one. But it isn’t the way, so far as concerns the Christian legacy.

Christian Realism

The sum of Niebuhr’s thought is often described as a Christian “realism.” It takes seriously the inevitability of sin and selfishness in human affairs, then seeks a set of social arrangements which provide a modicum of justice and the freedom for Christian witness to flourish.

Violence and war have a place in this. They have a certain necessity for him, though Niebuhr hardly had great confidence in their capacity for do-gooding. An adventure like the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which sought to transform a crumbling society into a model democracy through transformative violence, was hardly something he could get behind. But an intervention in Darfur against a coordinated genocide, more likely yes.

The trouble with Niehbur’s realism is its tendency toward fatalism. Indeed, he seems to realize this in the essay—it ends with a passage that appreciates the witness of pacifist Christians to the radical message of the gospel. Their voice, he accepts, can remind those who bear arms not to put too much trust in them. Niebuhr’s pressing concern, though, is to discredit those—like his former fellows in the FOR—who would call any willingness to fight wrongdoing with force a heresy.

But the consequences of fatalism are horrific in their own right. The nihilistic bombing raids that Allied bombers exacted on Germany and Japan reveal how complacency about the inevitability of war can easily slide into unbelievable brutality. And, immediately after, the reckless escalation of military industry in the Cold War only narrowly escaped self-immolation and delivered a condition of permanent, addictive militarism on the economy of the United States. Can these simply be written off as the inevitable wages of sin? Or shall we try harder to prevent such things from happening in the future?

Peacebuilding

“Blessed are the peacemakers,” Jesus said. Let us take this at face value, and forgive me for not probing the Greek etymologies (if English is good enough for Jesus, someone once said, it’s good enough for me). There is blessing in making peace, not simply in taking blows or constructing performances of resistance. Making peace can mean many, many things, depending on the time and place. Perhaps God leaves the means up to us.

Where I think the realist Niebuhr falls short is in the resources he provides for constructive peacebuilding action. He offers one set of negations—pacifism and passive resistance—against another—defensive war and a political order not dictated by religious commandments. For this reason he has become a darling lately for both neocons (like Michael Novak and David Brooks) against passivity abroad and planned economies, as well as liberals (like E.J. Dionne and Barack Obama) against military adventures and boisterous imperialism. But what is he for? What can he inspire us to do?

After putting a Niebuhr book down, one should be sure to go in search of those active in peacebuilding—fostering dialogue, providing for basic needs, erecting the infrastructure of justice—to counteract the excesses of his good sense. Efforts like these can be both pacifistic and realistic, both nonviolent and responsive. They fill in what he seems to leave out.

But that doesn’t mean peacebuilding—any more than pacifism or warfare—should become our religion, or be distilled as the essence of a religion. It is a tool of love, and a good one, though not to be mistaken for love itself.

]]> More on nonviolence. I hope this isn’t dull to some of you. To me it is an important conversation to have in anticipation of the new administration entering office, when any radical hope feels, for the moment, more thinkable than usual, more possible.

More on nonviolence. I hope this isn’t dull to some of you. To me it is an important conversation to have in anticipation of the new administration entering office, when any radical hope feels, for the moment, more thinkable than usual, more possible.

In several recent articles and posts relating to nonviolence (here, here, and here), I’ve been working in the space between the knowledge of evidence and the knowledge of faith. On the one hand, there is strong evidence and experience from around the world that Gandhian methods can work when employed by resistance movements against the powerful. On the other, the possibility of a U.S. foreign policy founded in Gandhian method is essentially untried; no powerful state, his own India included, has ever made a serious attempt of this kind. Consequently, I have suggested that this possibility lies more in the territory of faith. A faith-based initiative, so to speak.

Often, not to sound soft and fuzzy and sentimental, advocates for nonviolence have put their arguments in terms of science-y evidence. I have done the same with my DoNT project. We want to speak to the bureaucratic hunger for evidence that drives so much of our society. But I am also a watcher of religions and therefore know the hunger for faith that runs in people, often in places where talk of evidence lets it lie unnoticed. So, together with evidence, I think it very practical (and, incidentally, honest) to speak also of the faith that must support any effort to do what has never been done before. Again, the upcoming inauguration calls to mind faith in the never-before-seen all the more cogently.

Last night, in the final chapter of Gandhi’s Non-violent Resistance (Satyagraha), “The Future,” I discovered some remarks that speak to this quite clearly. It begins with questions to him by “a friend writing from America” who asks what will happen to nonviolence when India becomes an independent state. Won’t it simply revert to using violence as all other states do (and as India has)? Further, is it even possible for a state to behave nonviolently?

Gandhi concedes:

The questions are admittedly theoretical. They are also premature for the reason that I have not mastered the whole technique of non-violence. The experiment is still in the making. It is not even in its advanced stage. The nature of the experiment requires one to be satisfied with one step at a time. The distant scene is not for him to see. Therefore, my answers can only be speculative.

Very reassuring, to be sure, that the possibilities of nonviolent action were far from exhausted by a single man and a single movement. There are places yet to go, undiscovered countries to unveil. Still:

I fear that the chances of non-violence being accepted as a principle of State policy are very slight, so far as I can see at present.

That has certainly been true. Those who took power after Gandhi’s death were much more conventional types who lacked his vision, however much they admired and benefited from it. In the same short essay, he continues,

But I may state my own individual view of the potency of non-violence. I believe the State can be administered on a non-violent basis if the vast majority of the people are non-violent. So far as I know, India is the only country which has a possibility of being such a State. I am conducting my experiment in that faith.

I love that language here—”an experiment in faith.” Now I am no stranger to the troubles of mixing the language of faith with the language of science, but here, what else can be done? No experiment happens without faith. The failed “shock and awe” campaign in Iraq was an experiment conducted on faith, too. Since it was a disaster, the time has come to look for other faiths to try on ourselves.

In “The Future,” Gandhi goes on to describe how a nonviolent country would act in the face of an attack. It would be non-compliant. People would offer themselves to the cannons in the firm belief that something human lies within their opponent, probably suffering less in the end than if they had taken up arms. He concludes with disbelief about nations’ continued and unsupported faith in violence. Then something personal:

It gives me ineffable joy to make experiments proving that love is the supreme and only law of life. Much evidence to the contrary cannot shake my faith. Even the mixed non-violence of India has supported it. But if it is not enough to convince the unbeliever, it is enough to incline a friendly critic to view it with favor.

Those last words might sound familiar to none other than American evangelicals—they know that we are creatures who live not by bread alone, but by faith, and that where faith is concerned, rational evidences often aren’t enough.

]]>