As the movement matured, … it became common practice for occupiers to make reference to the guarantees of the First Amendment as they justified their actions to the public. The “Declaration of the Occupation of New York City,” passed by the General Assembly on September 29, states, “We have peaceably assembled here, as is our right.” It further calls on “the people of the world” to “exercise your right to peaceably assemble; occupy public space; create a process to address the problems we face, and generate solutions accessible to everyone.” The “Statement of Autonomy” passed on November 1 described the occupation as “a forum for peaceful assembly.” Meanwhile, lawyers working on behalf of the movement were trying to establish, on First Amendment grounds, the occupations’ legal right to exist — even as the constant police presence around the occupiers suggested that they had none. The “right” the legal documents spoke of were more an aspiration than a reality. Ultimately, however, the struggle didn’t play out on legal grounds; Zuccotti Park remained occupied mostly thanks to extra-legal pressures. When the city proposed to clean the park on October 14 — effectively a forcible removal — thousands of people arrived before dawn to stand in the way. A month later, when the eviction finally came, it was as a surprise in the middle of the night. The difference wasn’t so much legal as tactical.In the end, I think the "peaceable assembly" this movement is doing is less about the letter of the law than about a law inscribed in us elsewhere—in the conscience. Call be a bad lawyer. Or maybe just go ahead and call me an anarchist.]]>

Law, law, law. The other day I published an essay about the renegade lawyer William Stringfellow. Today I’ve got a new one at Harper’s?exploring what Occupy Wall Street has to do, if anything at all, with the First Amendment. Most people think it does, and I think they’re mostly wrong. Here’s a bit of it:

As the movement matured, … it became common practice for occupiers to make reference to the guarantees of the First Amendment as they justified their actions to the public. The “Declaration of the Occupation of New York City,” passed by the General Assembly on September 29, states, “We have peaceably assembled here, as is our right.” It further calls on “the people of the world” to “exercise your right to peaceably assemble; occupy public space; create a process to address the problems we face, and generate solutions accessible to everyone.” The “Statement of Autonomy” passed on November 1 described the occupation as “a forum for peaceful assembly.” Meanwhile, lawyers working on behalf of the movement were trying to establish, on First Amendment grounds, the occupations’ legal right to exist — even as the constant police presence around the occupiers suggested that they had none. The “right” the legal documents spoke of were more an aspiration than a reality.

Ultimately, however, the struggle didn’t play out on legal grounds; Zuccotti Park remained occupied mostly thanks to extra-legal pressures. When the city proposed to clean the park on October 14 — effectively a forcible removal — thousands of people arrived before dawn to stand in the way. A month later, when the eviction finally came, it was as a surprise in the middle of the night. The difference wasn’t so much legal as tactical.

In the end, I think the “peaceable assembly” this movement is doing is less about the letter of the law than about a law inscribed in us elsewhere—in the conscience. Call be a bad lawyer. Or maybe just go ahead and call me an anarchist.

]]>People have been thinking of proofs for the existence of God for millennia. Today's ongoing arguments conjure notions that date back to ancient Greece, the medieval monasteries, and Abbasid-era Baghdad. They come from some of history's greatest thinkers, polymaths who posited their proofs in the context of broader philosophical systems and bodies of reasoned knowledge. These people were generally less concerned to show whether a God exists or not – most assumed the answer to be yes – than to insist on the capacity of human reason to comprehend the universe. In our age of televangelists and monkey trials, the proofs have come to take on a different form altogether. They're the weapons with which atheists and believers battle for control of the public square in polemical tracts and newspaper op-eds. What was once the pursuit of obscurantist intellectuals has become a hobby for the rank-and-file, spawning an industry all its own. Recent decades have seen the creation of a whole crop of organisations devoted to promoting arguments for the existence or nonexistence of God. In the process, the meanings and ends of the classic proofs are being transformed.Don't miss the comments, which in The Guardian always reminds me of the ruckus at Speakers' Corner in Hyde Park.]]>

Today at The Guardian, a bit of a glimpse into my ongoing obsessions about proofs for the existence of God. Just last night, sifting through a novella I wrote as a freshman in college, I discovered a whole forgotten chapter about the proofs—for some reason, they have been following me so doggedly all these years. Today’s essay is something of a defense of those ancient proofs I love, against the caricatures that tend to speak for them today.

People have been thinking of proofs for the existence of God for millennia. Today’s ongoing arguments conjure notions that date back to ancient Greece, the medieval monasteries, and Abbasid-era Baghdad. They come from some of history’s greatest thinkers, polymaths who posited their proofs in the context of broader philosophical systems and bodies of reasoned knowledge. These people were generally less concerned to show whether a God exists or not – most assumed the answer to be yes – than to insist on the capacity of human reason to comprehend the universe.

In our age of televangelists and monkey trials, the proofs have come to take on a different form altogether. They’re the weapons with which atheists and believers battle for control of the public square in polemical tracts and newspaper op-eds. What was once the pursuit of obscurantist intellectuals has become a hobby for the rank-and-file, spawning an industry all its own. Recent decades have seen the creation of a whole crop of organisations devoted to promoting arguments for the existence or nonexistence of God. In the process, the meanings and ends of the classic proofs are being transformed.

Don’t miss the comments, which in The Guardian always reminds me of the ruckus at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park.

]]>I'm deeply committed to this collaborative process of talking and listening, writing and responding, editing and reflecting with my subjects. That's the least I owe them, and rather than discouraging a poignant or honest portrait, I think it often enhances my work. The courage it takes to write about people as I really see them, flaws and all, is related to the courage it takes for them to expose themselves, and then engage in the process of commenting on my portrayal. This congruency seems to support a certain sort of magic on the page -- a process of mutual pursuit of a truth, rather than a one-sided, hubristic claim on the Truth.It's a wonderful idea, one that has had a lot of appeal for me over the years in both journalistic and scholarly work. […]]]>

Recently on The American Prospect‘s website, Courtney E. Martin had a really thought-provoking short piece “questioning journalistic objectivity.” In it, she argues for a kind of journalism j-school professors would cringe at:

I’m deeply committed to this collaborative process of talking and listening, writing and responding, editing and reflecting with my subjects. That’s the least I owe them, and rather than discouraging a poignant or honest portrait, I think it often enhances my work. The courage it takes to write about people as I really see them, flaws and all, is related to the courage it takes for them to expose themselves, and then engage in the process of commenting on my portrayal. This congruency seems to support a certain sort of magic on the page — a process of mutual pursuit of a truth, rather than a one-sided, hubristic claim on the Truth.

It’s a wonderful idea, one that has had a lot of appeal for me over the years in both journalistic and scholarly work. By sharing drafts and exchanging ideas about the finished product, the writer can forge a deeper, more trusting relationship with the subject, with the goal of creating something they can both be proud of. I love it when the people I write about recognize themselves in what I’ve written, and I’m proud that they often say they do. It is more than a matter of accurate portrayal; when that happens, the two become partners in a common project greater than themselves.

Then again, it doesn’t always work out that way. Some people I write about purposely present a false image of themselves and expect me to promulgate it. Other times, I simply disagree with their position so much that my portrayal cannot in good conscience be as sympathetic as they’d like. Or their story, in the context of different perspectives, gets cast in a light they weren’t expecting. Collaboration, in these cases, might be challenging and instructive, but it also might be impossible.

Martin situates her argument in the context of a particular project.

I’m on the final stages of writing a book — a collection of profiles of ten people under 35 who are doing interesting social justice work. It’s been necessarily intimate; these are 8,000 word, very in-depth, largely psychological profiles. They require a level of openness, on the part of the subject, and a level of listening, on the part of the journalist, that surpasses any of the shorter, less personal genres.

One can see how a collaborative model would make so much sense here. She is writing about people whom she can get behind, whom she admires. If she doesn’t already feel a sense of shared purpose with one, I imagine, she wouldn’t include them in the book. But sometimes it is necessary, important, and beautiful to portray those for whom this isn’t the case. During my recent travels in Costa Rica, for instance, I went with the intention of finding people who I really could admire, whose stories we might craft together as collaborators. But what I found was that some of the most potent stories weren’t quite that way. My account could only be true to my experience if it diverged from that which the subjects would give of themselves.

In religious studies graduate school, I learned much the same methodology that Martin attributes to journalism school: collaborate with the subject so far as necessary to get the facts right, but don’t bring them into the process of analysis and synthesis. My professors distinguished between description and explanation. Subjects should recognize themselves in a description, but not necessarily in an explanation—that’s where the scholar takes control. Religion in particular, they taught, requires special care in this regard, since religious systems often provide their own self-explanations that don’t measure up to the standards of scholarship. Of course this is insanely arrogant to say, and we all knew it.

I would put the compromise this way: let writing be an encounter. Sometimes that encounter can be more collaborative than others. A published text can be part of a challenging conversation between writer and subject, and they may disagree about how it comes out. The writer’s responsibility is to stand in some awe before that encounter, taking seriously the transcendent otherness of the other. My purpose is not to stand in judgment, but to be curious, careful, artful, and true to experience. Not necessarily to Truth, which stands beyond even this profession, but at least to the truths that we are privileged to witness.

I almost never share a draft of an article with a subject. But I always try to send the finished product, asking for feedback, asking for a response, asking that it be considered. Often, they are the audience I care most about—not because I want to please them, necessarily, but because they did me the honor of speaking to me and I want to speak to them back. I hope that they will learn from what I write, not simply bask in it.

Martin situates her piece in the context of the present moment’s storied decay of journalism. She offers her approach as a new way forward. What I fear from it, though, is the even further convergence between journalism and public relations, wherein the independent press is traded for a dependent team of ghostwriters. That may be fine for Martin’s world-savers, but in other contexts, it won’t do. What journalism needs are people who are willing to give testimony to the inconvenient in ways that are also respectful and constructive, even if not always welcome.

]]>A good artist is a deadly enemy of society; and the most dangerous thing that can happen to an enemy, no matter how cynical, is to become a beneficiary. No society, no matter how good, could be mature enough to support a real artist without mortal danger to that artist.The Partisan Review's final question concerned the "the next world war." It asked, "What do you think the responsibilities of writers in general are when and if war comes?" Of all his answers, here Agee replies the most directly, the most earnestly, and the least aggressively toward the askers. He says he has thought much about the matter—“first glibly … later with more and more perplexity, distress, and immediate interest, fascination, and fear"—and several possibilities have come to him. […]]]>

A good artist is a deadly enemy of society; and the most dangerous thing that can happen to an enemy, no matter how cynical, is to become a beneficiary. No society, no matter how good, could be mature enough to support a real artist without mortal danger to that artist.

The Partisan Review‘s final question concerned the “the next world war.” It asked, “What do you think the responsibilities of writers in general are when and if war comes?” Of all his answers, here Agee replies the most directly, the most earnestly, and the least aggressively toward the askers. He says he has thought much about the matter—“first glibly … later with more and more perplexity, distress, and immediate interest, fascination, and fear”—and several possibilities have come to him.

- Enlist in that part of the war which seemed most dangerous, least glamorous, least relevant to any choice I might have through “education,” “class,” “connections,” or personal craftiness. This either for personal-“religious” reasons or out of an “artist’s” curiosity, or more likely both.

- Join the stalinist party and do as I was told or Bore from Within it. [A page earlier he writes, “‘I find, in retrospect,’ that I have felt forms of allegiance or part-allegiance to catholicism and to the communist party. I felt less and less at ease with them and am done with them.”]

- Stay wherever I happened to be, mind my own business, refuse every order, and take the consequences.

- Stay wherever I happened to be, and write what I thought of the War, the Pacifists, etc., wherever I could get it printed.

- Escape from it by whatever means possible and by the same means continue to do my own work.

For those of us hoping to plant Agee in a particular position or camp, either for or against this war or war in the abstract, he is evasive. Even the pacifist crowd, so radical in its way, he considers also a “society” into which an artist cannot afford to blend. Answer 1 offers a very Christ-like self-sacrifice, venturing among the least to reveal the truth for all. But, unlike number 3, and possibly numbers 2 and 4, it seems a perfectly anti-political position to take. So also is number 5. Taken together, though, the options offer little assurance to the partisan.

A footnote appended later seems to be some encouragement for radical nonviolence:

I would now (fall of 1940) have to add to this belief in non-resistence to evil as the only possible means of conquering evil.

Only to equivocate in the very next sentence:

I am in serious uncertainty about this belief; still more so, of my ability to stand by it.

If you’re tempted to dismiss Agee as simply a political weakling, a dilettante making games out of serious business, the last sentences of this section are worth hearing out. They spell out a cosmic reversal, an insistence that The War everyone talks about is in fact a game, an absurdity when viewed from the truly serious business of making art and meaning for the human race.

Or, in other words, I consider myself to have been continuously at war for some years, and can imagine no form of armistice. In that war I feel “responsible.” I doubt any other form of war could make me more so.

This artist, he insists, cannot be the partisan that the Review wants to drum out concerning the coming war. He refuses to accept the war being declared by politicians and generals—and all manner of those who consider themselves informed—as the real war most worthy of his attention. Especially when no one else does, the artist can look past her or his society’s present means of mass suicide and murder, into the deathless questions that, by being ignored, so provoke the rest of us.

During World War II, Agee devoted himself to reviewing films for Time and The Nation. The draft board passed him over. He had a son who died soon after being born, and he married his third wife.

]]>We live in a Dark Age, and have, for several thousand years. It is time for a renaissance—with the wisdom of the past. … Augustus Le Plongeon calls architecture an unerring standard of the degree of civilization reached by a people, "as correct a test of race as is language, and more easily understood, not being subject to change." If it is true that a nation's capital reflects its standards of architecture, we risk being judged by the phony cyclopean walls of the Office Building of the U.S. House of Representatives unless we engender architects sensitive to the cosmic values of geometry, such as R. Buckminster Fuller would envisage. The ancient civilizations attached great importance to numbers as an exact language in which physical and spiritual ideals could be expressed and preserved; hence, they built numbers into their buildings.[…]]]>

Being sick in bed on this Christmas Eve in San Cristobal de las Casas, Mexico has afforded me the welcome opportunity to spend the day with Peter Tompkins’s Mysteries of the Mexican Pyramids. Tompkins, a journalist, World War II spy, and occult theorist (AP obituary; profile), was a fixture in the background of my childhood. His 1971 classic Secrets of the Great Pyramid (Mysteries came later, in 1976), was given to me by my uncle, like most of his gifts to me, at an age when I was still far to young to know what to do with it. So the book sat on my shelf, tantalizing with its mathematical diagrams and antique woodcuts.

Being sick in bed on this Christmas Eve in San Cristobal de las Casas, Mexico has afforded me the welcome opportunity to spend the day with Peter Tompkins’s Mysteries of the Mexican Pyramids. Tompkins, a journalist, World War II spy, and occult theorist (AP obituary; profile), was a fixture in the background of my childhood. His 1971 classic Secrets of the Great Pyramid (Mysteries came later, in 1976), was given to me by my uncle, like most of his gifts to me, at an age when I was still far to young to know what to do with it. So the book sat on my shelf, tantalizing with its mathematical diagrams and antique woodcuts.

The gist of Tompkins’s view of the universe comes out in his preface to Mysteries:

We live in a Dark Age, and have, for several thousand years. It is time for a renaissance—with the wisdom of the past.

… Augustus Le Plongeon calls architecture an unerring standard of the degree of civilization reached by a people, “as correct a test of race as is language, and more easily understood, not being subject to change.” If it is true that a nation’s capital reflects its standards of architecture, we risk being judged by the phony cyclopean walls of the Office Building of the U.S. House of Representatives unless we engender architects sensitive to the cosmic values of geometry, such as R. Buckminster Fuller would envisage.

The ancient civilizations attached great importance to numbers as an exact language in which physical and spiritual ideals could be expressed and preserved; hence, they built numbers into their buildings.

Next, the book jumps into nearly two hundred riveting pages on the story of how Europeans gradually came to grasp the significance of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican civilization, from Cortes to the Romantic archaeologists. Tompkins relishes in details and tangents, which come out especially in the extended picture captions, sometimes spanning entire pages. Nearly every page includes a picture or two, whether it be a period drawing of Tenochtitlan as the conquistadors saw it or a portrait showing just how handsome Alexander von Humboldt was. The relationship between text and image has much in common with the hardcover version of Carl Jung’s Man and His Symbols, an old favorite of mine.

Where Tompkins really shines, though, are the chapters grouped under the heading “scientific analysis.” Here, charting all sorts of alignments among the pyramids against geography and the stars, he spells out his conviction in evidences that something very deep indeed was at work in the ancient structures. Unfortunately, these are the parts least engrossing to my temperament, so for today I am content to merely admire their form and effect rather than delving into the actual claims. Over the years I’ve seen some arguments from trustworthy authorities that Tompkins’s claims of ancient sophistication are overblown. So I can’t let myself take it all too seriously, only to enjoy the accomplishment.

Where Tompkins really shines, though, are the chapters grouped under the heading “scientific analysis.” Here, charting all sorts of alignments among the pyramids against geography and the stars, he spells out his conviction in evidences that something very deep indeed was at work in the ancient structures. Unfortunately, these are the parts least engrossing to my temperament, so for today I am content to merely admire their form and effect rather than delving into the actual claims. Over the years I’ve seen some arguments from trustworthy authorities that Tompkins’s claims of ancient sophistication are overblown. So I can’t let myself take it all too seriously, only to enjoy the accomplishment.

Throughout the foregoing, Mysteries drops hints here and there of similarities with other ancient civilizations in Egypt and Mesopotamia, as well as the occasional mention of Atlantis. In the book’s final section of chapters, though, Tompkins takes on these concerns outright, without flinching. Here he reveals himself as an all-out New Age enthusiast (see his aptly-named son Ptolemy’s memoir on the subject). Ancient Mesoamerican civilization, Tompkins believes, was likely seeded by seafaring Phoenicians who came by way of the mythical continent of Atlantis. Part of the evidence for this he takes from the visions of the great twentieth century psychic Edgar Cayce. I kept wondering why his credulity fell short of that beloved occult fad of the 70s, ancient, alien astronaut theory.

Regardless of how silly this all might sound to the sober-minded among us, I promise that Mysteries of the Mexican Pyramids makes fantastic sick-day reading. Maybe even healthy-day. What one has to love about Tompkins, in addition to his virtuosity with words and pictures, is his powerful sense of trust in cosmic truth and in that truth’s ability to make us better. This, combined with the gusto of a spy, makes knowledge into life’s greatest adventure. From the dedication of Mysteries, one can imagine Tompkins at work, an Indiana Jones who knows that truth comes only to those willing to get their hands dirty.

]]>To the staff of the Library of Congress, guarantors of free access to the sources, without which enjoyment of the First Amendment to the Constitution could be reduced to an exercise in vacuo.

Last night, while waiting for a friend at the corner of Lafayette and Bleeker, I learned that to stand at a busy corner near a Manhattan subway entrance means becoming a directions machine. In the course of half an hour, maybe eight people asked me for directions. I’m a guy with a pretty good sense of direction, so in every case I knew the answer, and I told them. Then, at the end, I got out the map that I was carrying in my sack all along. Turns out, half the directions I gave were at least somewhat wrong. Worst of all was this exchange where I was asked where Mercer Street is, and I pointed north up Lafayette, having some memories of Mercer close to NYU. But a woman walking by shouted out, No way, it’s down south of here. I said, Fine. Well of course, a few minutes later I learned Mercer is parallel to Lafayette, two blocks to the west. Both of us, in all our certainty, were dead wrong.

Last night, while waiting for a friend at the corner of Lafayette and Bleeker, I learned that to stand at a busy corner near a Manhattan subway entrance means becoming a directions machine. In the course of half an hour, maybe eight people asked me for directions. I’m a guy with a pretty good sense of direction, so in every case I knew the answer, and I told them. Then, at the end, I got out the map that I was carrying in my sack all along. Turns out, half the directions I gave were at least somewhat wrong. Worst of all was this exchange where I was asked where Mercer Street is, and I pointed north up Lafayette, having some memories of Mercer close to NYU. But a woman walking by shouted out, No way, it’s down south of here. I said, Fine. Well of course, a few minutes later I learned Mercer is parallel to Lafayette, two blocks to the west. Both of us, in all our certainty, were dead wrong.

The realization hit me like, what… the punch that killed Houdini? If I spread all those incorrect (though innocent, rather inconsequential) factoids, what more have I missed without knowing I missed it? Not least, because of the mythical importance giving accurate, precise directions has in my paternal line. But more immediately troubling, as a writer, what accidental falsehoods have I set down and published?

Since first grade, when this kid named Seth fooled me up and down all the time, I’ve known that just about always I’m the most gullible person in the room. The result of being an only child, perhaps. Tell me anything and I’ll believe it, unless you really, really overdo the sarcasm. Or unless I’m massively prepared by some aloof posturing. Probably this is why I ended up getting into studying religions—I have a peculiar fascination with getting inside the beliefs people adopt. Constantly in this work I feel myself being drawn into them, then sneaking out. Viscerally, being gullible feels like the mechanism at work in my bad direction-giving as well. It is the same willingness to believe the first thing that pops up as a possibility.

Wikipedia has a great list of cognitive biases, many of which are pertinent here and have better, more scientific names than “gullibility.”

I recently spoke with a reporter at The New York Times, who in many ways seemed to have the opposite dispositions. His background is as a big-city police reporter, investigating crooked crooks and crooked cops. Now, having been placed on the religion beat, the habits of suspicion he learned on the police beat carry with him. He told me that when he sees a lot of big-shot pastors, he says they look an awful lot like the mob bosses he used to know. It’s hard to get past that, he said, but it does push him to dig deeper, to ask more questions, to get to the bottom of it all.

My tendency is otherwise. I’m usually content with the first things I discover about an issue, or with the bad guys’ public rhetoric. For me the fun is in the interpretation, in crafting the raw material into a story. But the more I do this work of writing about others, the more respect I have come to have for the facts. Particularly writing for the internet, where interpretations are a dime a million, facts are what can turn a story upside down. Or “evidences,” as the 19th century theologians used to say—until Darwin came along, at least.

So I’ve been trying to initiate myself into the cult of suspicion—suspicion of my own beliefs and of the claims that others make. A suspicion that will force me to ask more questions, suspect my own impressions, and go beyond the veneer of lies that covers most everything in public life.

At the same time, though, there is something peculiar in the study of religion that makes gullibility a virtue. When you’re dealing with religions, there is always an important truth to be found even in the coarsest lies. These aren’t truths that would be admissible in court, perhaps, but they’re human truths nonetheless. What they convey is part of the religious state of affairs, and it cannot be ignored. To see those truths, buried as they are in plain sight, it helps to be willing to try any old belief for size. It helps to be gullible.

Giving decent directions, however, is quite different.

]]>For if we do not persist in the quest for intelligibility, there can be no human sciences, let alone, any place for the study of religion within them.[…]]]>

Perhaps philosophy today has taken its cue from a world that believes ideas need not be taken seriously. They can be replaced, the policy goes, with stuff like enjoyment, the market, and values. Or else, ideas are simply a subset of those. I myself have argued at times that philosophy might simply be reducible to friendship. In The New Republic, Adam Kirsch has just written a powerful attack on the academy’s embrace of Slavoj Zizek, whom Kirsch makes out to be a dangerous fascist clown in favor of everything the 20th century taught us not to do. The apotheosis of this embrace, in my eyes, was seeing a paper delivered to an evangelical audience at the American Academy of Religion meeting this year (the panel started with a prayer), which excitedly used Zizek as a tool for resurrecting evangelical politics. If a hip, handsome evangelical pastor can love Zizek, anyone can. And by taking the clown for a responsible thinker, have we forgotten that ideas have real, decisive consequences?

Perhaps philosophy today has taken its cue from a world that believes ideas need not be taken seriously. They can be replaced, the policy goes, with stuff like enjoyment, the market, and values. Or else, ideas are simply a subset of those. I myself have argued at times that philosophy might simply be reducible to friendship. In The New Republic, Adam Kirsch has just written a powerful attack on the academy’s embrace of Slavoj Zizek, whom Kirsch makes out to be a dangerous fascist clown in favor of everything the 20th century taught us not to do. The apotheosis of this embrace, in my eyes, was seeing a paper delivered to an evangelical audience at the American Academy of Religion meeting this year (the panel started with a prayer), which excitedly used Zizek as a tool for resurrecting evangelical politics. If a hip, handsome evangelical pastor can love Zizek, anyone can. And by taking the clown for a responsible thinker, have we forgotten that ideas have real, decisive consequences?

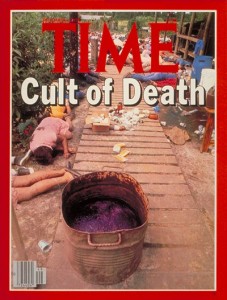

Meanwhile, in honor of the 30th anniversary of the Jonestown mass suicide, I’ve been struggling to know what ideas can do in the face of horror. This, with Jonathan Z. Smith’s insistence at the end of his essay, “The Devil in Mr. Jones,” that the whole promise of the human sciences rests on their hope of giving an answer to what happened there in 1978:

For if we do not persist in the quest for intelligibility, there can be no human sciences, let alone, any place for the study of religion within them.

In the comments over at Larval Subjects, there is a pretty good start to a reply to Kirsch’s essay.

First, the article fails to mention Zizek’s oft-repeated statements about choosing the “bad alternative” as a way of shifting the very co-ordinates of the debate. In other words, the aim is not to advocate the “bad” position as the review suggests, but rather to shift the terms of the debate and reveal the hidden assumptions that underlie the debate. … Second, nowhere does the review outline Zizek’s arguments against liberal democracy.

What Kirsch does do, though, is show that Zizek is a man at play. While walking the walk of a successful bourgeois philosophy professor, he manages to talk the talk of a violent revolutionary, calling for a return to Leninism and Maoism and the destruction of liberal democracy. Whole traditions like Christianity and Judaism are reducible to nugget-like principles, which make them and their adherents candidates for eradication if necessary. If Kirsch is right, Zizek has forgotten that ideas have serious consequences and thinks, quite nihilistically, that he can toy with them however he wants and however he can attract attention. If Larval Subjects is right, Zizek believes we need to be shaken into a new willingness to take ideas seriously as offering alternatives to the world order. Even if the latter is so, however, how much will Zizek take responsibility for the horror his proposals might create?

I am no Zizek, but the method I am trying to develop in the study of religion has resonance with his. I try to toy with ideas wherever they go, whatever their consequences may be. Though I suspect that creationism is false and possibly dangerous, for instance, in my research I am most interested in uncovering the truth in it. Following J. Gordon Melton, I refuse to label even the most troubling new religious movements as “cults”—and therefore as fundamentally different from mainstream established religions. It is, in this sense, a kind of a-moral method. In the process, I rest my faith on a principle of intellectual nonviolence: seek the truth everywhere and in the end goodness will prevail. Like Zizek, according to the Larval Subjects reading, I want to shake my readers out of their own assumptions and worlds, into the possibility of another.

But, after watching the excellent PBS documentary on Jonestown, I was struck by the feeling that my method had real shortcomings in the face of this event. What can I do but sympathize and explore? My way of taking Rev. Jones’s ideas seriously would be to find the truth and resonance in them, rather than opposing every resemblance to them, wherever it might appear. Do I have to go further? This comes to mind, especially, as I write about Harun Yahya, the Turkish creationist who may or may not be guilty of some rather Jones-like crimes.

Does “taking seriously” mean a wagging finger against dangerous ideas or a reckless foray into them?

]]> Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Travels with Herodotus came to me as a birthday present in the beautiful Adirondacks in August. Not till the last couple of weeks, while traveling in Turkey and Jordan, did I get the chance to read it. The timing, as it turned out, was just about perfect.

Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Travels with Herodotus came to me as a birthday present in the beautiful Adirondacks in August. Not till the last couple of weeks, while traveling in Turkey and Jordan, did I get the chance to read it. The timing, as it turned out, was just about perfect.

I wouldn’t call it a great book so much as deeply and earnestly good. It speaks to me less as fine literature than as the rambling talk of a grandfather with more advice to me in his words than he quite seems to know.

Kapuscinski, a Pole whose youth was made of death by World War II, set off in the mid-fifties on a lifelong career as a foreign correspondent that took him all over the world. Earlier books of his, advertised on the back pages, include chronicles of the Iranian revolution and the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Travels with Herodotus, Kapuscinski’s last book before his death in 2007, is both grander and more minute in scope than those. He recounts stories from Herodotus’s Histories—the ancient world’s most important picture of itself—against the backdrop of moments, mostly little and uneventful ones, from his own career.

From when Herodotus’s book was given to him at the start of his first assignment, he nearly always brought it along, reading and rereading. In a manner that is anything but scholarly, he claims Herodotus not as the first historian, as is conventional, but the first journalist.

What propelled him, fearless and tireless as he was, to throw himself into this great adventure? I think it was an optimistic faith, one that we men lost long ago: faith in the possibility and value of truly describing the world. (p. 259)

Like Herodotus’s book, Travels lets the past and present mingle together, unable to say which is the more real.

The most affecting chapters for me were the early ones, which tell of Kapuscinski’s first assignment in India. He arrived knowing nothing of the place and with only a few words of English at his command, yet he was expected to report its goings-on for the Polish press. For Herodotus, too, India is the very limit of the known earth, and his reports betray more gullibility than knowledge. The two, ancient Greek and modern Pole, report on India naively together.

I was right there with them. As I read, I was on my first trip abroad on assignment, and my main preoccupation was not to betray how little I knew what I was doing. But the journey opened worlds. And it was incredibly fun. Being in these places, seeing their details, lent me a new admiration for simple facts, the tiny incontestables that are so plain to see and so easy to report if only there is someone to do so. This world of human beings, where the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing, starves for simple facts.

I was right there with them. As I read, I was on my first trip abroad on assignment, and my main preoccupation was not to betray how little I knew what I was doing. But the journey opened worlds. And it was incredibly fun. Being in these places, seeing their details, lent me a new admiration for simple facts, the tiny incontestables that are so plain to see and so easy to report if only there is someone to do so. This world of human beings, where the right hand doesn’t know what the left hand is doing, starves for simple facts.

Since I began working toward writing for a living ten months ago, I’ve been calling myself, vaguely, a writer, thinking of the work as mainly interpretation mixed with art. But as the plain facts began to present themselves, and before I was halfway through Kapuscinski’s book, I decided to join him and his Herodotus in their particular compulsion and its service to the world. When asked, while gathering, collecting, and assembling, I’ve begun saying that I am a journalist.

]]>Hello Nathan: One piece of information which I did not notice in the discussion was the fact that this multi-verse is a virtual reality which is being displayed in a virtual 3D monitor. That's the reason that space, time, mass and energy are quantized. The omission of this fact (that this is a virtual reality) distorts the logic tree from what it could and should be. The distorted logic tree causes less-than-optimum choices seem to be optimum. The entire discussion therefore need to be revised. Thanking you for your attention to this topic, *****[…]]]>

Hello Nathan:

One piece of information which I did not notice in the discussion was the fact that this multi-verse is a virtual reality which is being displayed in a virtual 3D monitor. That’s the reason that space, time, mass and energy are quantized.

The omission of this fact (that this is a virtual reality) distorts the logic tree from what it could and should be. The distorted logic tree causes less-than-optimum choices seem to be optimum. The entire discussion therefore need to be revised.

Thanking you for your attention to this topic, *****

Not knowing quite what to say, I replied thus:

Dear *****,

Wonderful name and wonderful note. You’re right—surely there are many, many ways in which all of us are operating under false premises of some kind. Even the smallest, in their endless permutations, can render what we know nothing more than silliness.

Forgive me for failing to mention virtual reality.

yours,

Nathan

To which he was kind enough to answer back:

Hello Nathan:

Insofar as it is within my authority to forgive somebody for something, I would gladly forgive you of the oversight to mention that this multi-verse is a virtual reality which is being displayed in a virtual 3D monitor, provided that you were to follow the logic tree, which includes that fact, to its proper conclusion. This proviso is not for my benefit. It’s for yours.

Hoping that this additional discussion is of interest and benefit, *****.

It is a strange world out there, and a neat thing about writing is that people, in reply, can point one toward new and worthwhile dimensions of strangeness.

]]> I guess Cicero was the original flip-flopper. Since following him in a recent boat of watching the HBO/BBC TV series, Rome, I've been reading up on the guy who before I've mainly known from heresay—from the pens of Augustine, Montaigne, etc. It was disappointing to see that the show had no interest in Cicero's (or anyone else's) life in ideas, but its depiction of him as politician still caught my eye. Though it seems that there are the inevitable historical inaccuracies (such as his role in the Senate during the rule of Julius Caesar), Rome's general gist of the man seems right: he was easily swayed and never convinced, and he didn't stand up for his convictions—which is a thing people, and particularly politicians, are supposed to do. […]]]>

I guess Cicero was the original flip-flopper. Since following him in a recent boat of watching the HBO/BBC TV series, Rome, I've been reading up on the guy who before I've mainly known from heresay—from the pens of Augustine, Montaigne, etc. It was disappointing to see that the show had no interest in Cicero's (or anyone else's) life in ideas, but its depiction of him as politician still caught my eye. Though it seems that there are the inevitable historical inaccuracies (such as his role in the Senate during the rule of Julius Caesar), Rome's general gist of the man seems right: he was easily swayed and never convinced, and he didn't stand up for his convictions—which is a thing people, and particularly politicians, are supposed to do. […]]]> I guess Cicero was the original flip-flopper. Since following him in a recent boat of watching the HBO / BBC TV series, Rome, I’ve been reading up on the guy who before I’ve mainly known from heresay—from the pens of Augustine, Montaigne, etc. It was disappointing to see that the show had no interest in Cicero’s (or anyone else’s) life in ideas, but its depiction of him as politician still caught my eye. Though it seems that there are the inevitable historical inaccuracies (such as his role in the Senate during the rule of Julius Caesar), Rome‘s general gist of the man seems right: he was easily swayed and never convinced, and, besides the lost dream of the republic, he didn’t seem to have convictions—which is a thing people, and particularly politicians, are supposed to have.

I guess Cicero was the original flip-flopper. Since following him in a recent boat of watching the HBO / BBC TV series, Rome, I’ve been reading up on the guy who before I’ve mainly known from heresay—from the pens of Augustine, Montaigne, etc. It was disappointing to see that the show had no interest in Cicero’s (or anyone else’s) life in ideas, but its depiction of him as politician still caught my eye. Though it seems that there are the inevitable historical inaccuracies (such as his role in the Senate during the rule of Julius Caesar), Rome‘s general gist of the man seems right: he was easily swayed and never convinced, and, besides the lost dream of the republic, he didn’t seem to have convictions—which is a thing people, and particularly politicians, are supposed to have.

Cicero switched sides at a crucial moment, and in ignominy—he transferred his allegiance from Pompey to Caesar, begging forgiveness from the new emperor. He could never quite commit himself to any position.

I suspect, indeed, that Cicero’s flip-flopping cannot be understood without his philosophy—which is why he is such a strange character in the TV show. An eclectic skeptic, skeptical even of skepticism, the richness of his ideas seem to have undermined his political career.

Another case of a similar thing arises in a passage from Michael Novak’s forthcoming book about New Atheists, which I am currently in the process of reviewing:

In times of stress, distinguished intellectuals such as Heidegger and various precursors of postmodernism (including deconstructionist Paul de Man) displayed a shameless adaptation either to Nazi or to Communist imperatives—or to any other anti-Hebraic relativism. Even elites may lose their moral compass. (No One Sees God, p. 53)

It is a terrifying thing in Cicero and in folks like Heidegger, something I can only call a sin, and yet a sin I want so much to transform into a workable virtue.

No great conclusions from me tonight. These examples touch on issues that I’ve been toying with a lot lately: The Politics of Cowardice | Different Sorts of Skepticism | Becoming a Person — and so on. The problem is this: how does a person keep an open mind and see truth in different sides while remaining a coherent person, and more, a fighter for good?

]]>